The judiciary believes that desire consolidates at the legal age of maturity and consequently defines consent around the same parameters. Thereby reaching the conclusion that an individual below 18 is not capable of sexual desire therefore cannot consent to sexual activity since they legally do not fall under the category of an adult.

Does childhood then end abruptly at 18 or is a legally underage individual not a desiring subject? This schizophrenic model of sexuality has had bizarre consequences for the society, especially for women who enter into the institution of (emphasis on) arranged marriage.

Independent Thought, an organization working for the rights of women and children, filed a written petition before the Supreme Court challenging Exception 2 to Section 375 of the IPC to the extent of its applicability in case of minor girls. The Exception, more commonly known as the Marital Rape exemption, states that a man cannot be charged with rape of his wife provided the wife is not below 15 years of age.

By law, a woman metamorphosizes into a desiring subject, a nymph preferably, overnight once she turns 18. Until then the law protects her like a father. The POSCO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) Act, 2012 punishes any man even the husband attempting to make conjugal relations with the minor. The woman has no say in the matter given that she is still a child, incapable of desire, untouched, innocent, virgin- promoting erasure of consent for the awkward category of the ‘girl-wife child’.

Now the day you turn 18, the law shall not protect you from unreciprocated advances from your husband-shooting the so-called phenomenon of ‘marital rape’ in the head.

What is interesting here is that in both the cases consent is beautifully played against women. Before 18 they CANNOT consent (within or outside marriage) and after 18 there is no consent within the marriage.

While in the former case the law has no problem intervening and meddling with the ‘sanctity’ of marriage in the latter, it is precisely this argument that deters them from acknowledging the fact that most women do not want to and therefore are forced to have sex with their husbands.

Independent Thought vs Union of India is a perfect example of how the judiciary reads a child, forcing us to rethink the meaning of the category ‘child’.

Does it pit the category of the girl child against them? Considering the state choses to protect the girl child but not women who are similarly aggrieved or does age alter the intensity of trauma and rape? Is the rape of a 15-year-old more traumatic than that of a 45-year-old?

This delineation does little in my opinion to assuage the threat of sexual violence within marriage or prevent child marriages either.

It does little, in my opinion, to assuage the threat of violence within the institution of marriage or protecting girl children from early marriages either. It only makes women more vulnerable to abuse by creating this neoliberal split between women and girl children in the legal framework.

I say neoliberal considering the socio-economic reality of the lives of women in places like India- given the class and caste markers.

In most communities girl children are hardly raised as children especially in the context of communities where early marriages are common.

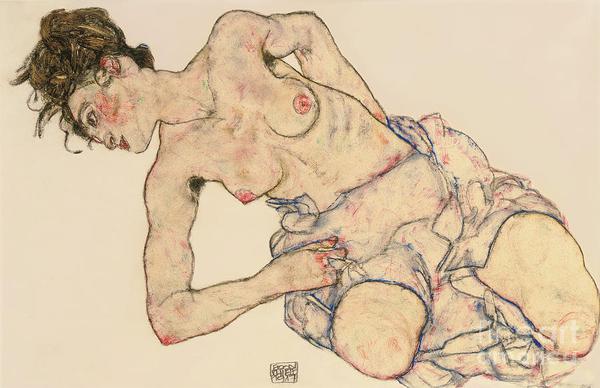

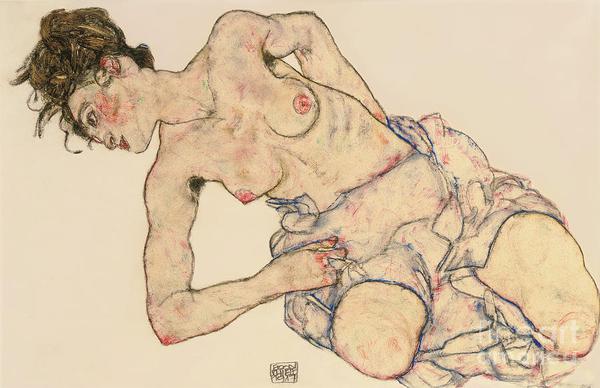

In a society where the woman is seen fit culturally to bear the responsibility of the household before 18, why is she then treated like a child in the bedroom? Why is it difficult to conceive her as capable of desire when she is biologically and psychologically equipped to act on it. This makes us question consensual sexual acts outside marriage as well- the model of desire is clearly sanitised in law.

Along the same tangent consider the minor who raped a legally adult woman such as in the Nirbhaya case, where does that take us along the capability model?

Does this mean that understanding the human is beyond the legal- atleast today. Or is it symptomatic of a lag within the legal interpretation that demands a radical break from our conventional sensibilities? If we are to deal with the perils of ‘consent’ as a category for demarcating desire from violence, we need to re-evaluate what each of these signifies, not just in the symbolic but material and sociological order before translating them into legal definitions.